I used to think of leadership as simply an unquantifiable attribute applied to anyone in a management position, something to fill out a resume or list of job qualifications: must demonstrate accountability, proficiency with worksheet-based applications such as MS Excel, and leadership. I disregarded leadership. It wasn’t something to be consciously developed, and because of this, I dismissed its importance.

However, I’ve learned that dismissing the importance of leadership in a company is tantamount to dismissing the importance of every employee at that company.

Would you tell Karen in accounting that she is easily replaceable? Would you qualify the new business team titles as “just” sales people? Would you commiserate when an employee expresses frustration about other people in your organization?

A leader would answer “no” to these questions.

As a burgeoning leader, I’ve recently taken a much more conscientious approach to understanding the important role that leadership plays. I’d like to share a few paradigm-shifting realizations I’ve made recently.

1. Two heads are better than one

Three heads are better than two. Four heads are better than three. And on and on.

Getting things done alone is possible. But it’s incredibly difficult…and incredibly ineffective when looking for long-term results. Last year, here at GLI we changed the organization structure in a way that allowed myself and Michael Solms to work much more closely. Before this pairing, I didn’t realize that some of the frustration I was feeling (we all have work-related frustrations, admit it) was because I was speaking in favor of change without the direct support of like-minded people.

Get a Free Analysis of Your Website

I’ll give an example (lest you assume I’m speaking of frustrations much larger than they really are). I’ve long yearned for a reliable time-tracking solution at GLI. Without accurate time-tracking, an organization lacks a critical piece of decision-making information. We’ve had time tracking, but the ability to report was rife with hurdles. I felt a better system was needed.

Once Michael and I started working together, and as we developed a wonderful working relationship, my desire for time-tracking became our desire for time-tracking.

This idea of shared motivations became even more powerful when we set out to refine and reintroduce GLI’s Purpose, Mission, and Values. With shared guiding principles, time-tracking isn’t a question about whether or not we need it, but whether or not it aligns with our values (And it does. Value #2. We strive to base all decisions on data). Shared values mean shared accountability which makes buy-in from multiple parties much easier. When everyone agrees with a decision (or has at least had a chance to understand the reason for a decision), the effects will be longer-lasting.

2. Eradicate all assumptions

Everyone in the office gets tired of me repeating this phrase: eradicate all assumptions. The idea is simple: anything assumed means unnecessary worry. Why stress wondering if you heard the client correctly about a specific deliverable? Why worry about whether or not a co-worker understands that your need for a report is urgent? Why spend hours building a spreadsheet on the assumption that you understood the client’s intended use case? Why should you have to be burdened by someone else’s unclear information?

Never, never, never assume. State your expectations and understanding, and ask that others do the same.

Practically speaking, this includes:

- End each meeting with specific action items and due dates

- If you don’t understand a chart, don’t assume you’re missing something and that you’ll figure it out later (“Why should you have to be burdened by someone else’s unclear information?”)

- Don’t let someone get away with being passive-aggressive. It’s not your burden to interpret the emotions of others.

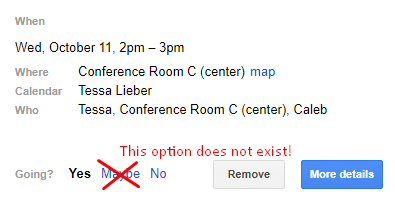

- Click Yes or No on a meeting invite (I wish all calendar programs would eliminate the Maybe option)

Of course, eradicating assumptions logically means you’ll have to…

3. Force yourself into uncomfortable situations. Be proximate.

A leader recognizes discomfort as a symptom of friction (and friction as a symptom of a problem that needs fixing). A responsible leader is not satisfied to let that friction fester into a workplace cancer.

Perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned recently about leadership is that uncomfortable situations are only uncomfortable because of inaction. We see this play out often when public figures are forced to apologize for various wrong-doings. A politician says something stupid, for example, and there’s a clear connection between the quickness to apologize and the believability of his/her remorse. The sooner the “I’m sorry” the more willing we are to accept it. Why? Stepping into uncomfortable situations is a strength that we respect (even when the discomfort is self-inflicted). We understand the inherent need for action amidst discomfort.

Nobody enjoys confronting an employee about poor performance. But a leader understands that such confrontation is integral to the employee’s professional development (and more-so, a leader understands that nothing is more important than the success of your employees).

4. Never stop learning

(Never stop reading, specifically, but the occasional TED Talk video is worth your time as well).

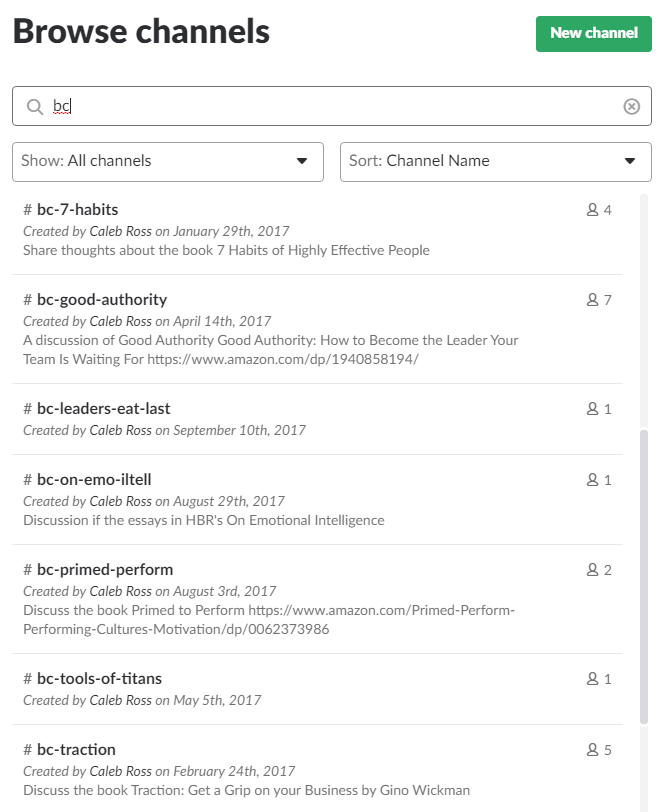

Primed to Perform: How to Build the Highest Performing Cultures Through the Science of Total Motivation taught me to reframe my understanding of motivation, from a tool to get work from people into what it really is: a way to help others care about the work they do. Good Authority: How to Become the Leader Your Team Is Waiting For taught me about delegation as a critical means for empowering others to grow and be accountable. I thought I was helping by taking on more work. It turns out, I was preventing other people from becoming great at their jobs. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change taught me about expanding my circle of influence and creating buy-in from people who are impacted by decisions. The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom showed me how poisonous assumptions can be.

But you don’t have to do all the reading yourself. Ask others what they are reading. Start a book club at work (here at GLI we create Slack channels where we keep notes and maintain the discussion. Everyone at GLI is free to join in).

A discussion does many things simultaneously:

- It holds others accountable to continued learning

- It allows others to contextualize the content of the books (which is an important part of learning)

- It allows others to reveal their excitement and passions

- It allows you to learn important points quickly

Did you notice that I didn’t include any selfish reasons until the final item on the list? Afterall, Leaders Eat Last.

Part of being a leader is developing the ability to recognize leadership potential in others. Nothing–and I’ll repeat it just so you know I’m serious–nothing has allowed me greater visibility into the potential leadership of others than their bookshelves.

I’ll end with a simple summarized list:

- Get buy-in for important decisions

- No assumptions. Ever.

- Discomfort means you recognize an opportunity to be a leader. Seize that opportunity.

- Read. Read. Read.

So tell me, what are you reading?